There was already a class division in the tribal structure of the Aryans when they entered India. However the social divisions became more prominent in the Vedic period due to the racial discriminations between the Aryans and non-Aryans, who after being defeated by the former were treated as Dasas, Dasyus and shudras. Gradually the tribal society of the Aryans were divided into three classes or groups –the priest (Brahmanas), warrior (Kshatriyas) and peasant (vaishyas).

The purusha shukta or creation Hymn of the Rigveda (X, 90, 12) says that Brahmanas, Kshatriyas, vaishyas and shudras originated respectively from the mouth, arms, thighs and feet of the Purusha or Creator. This hymn is taken to be the root of caste system in India. But initially it was varna (literary means colour) and referred to the person of a particular profession, and not of particular birth.

But in the hymns of the Rigveda rigid restriction typical of castle in its mature form is not evident. There is no trace of any restriction on marriage, food and drinks. There were different classes and professions but none, not even the priestly or warrior classes were hereditary. Any person, irrespective of his Varna, who possessed the requisite qualifications, could officiate as a priest and anyone could join the army. In one Rigvedic family the father, mother and the son followed three different vacations viz, those of a poet, a grinder of corn and a physician. Thus if in one family the occupations of the son, the father and the mother were different, a hereditary caste system based on different kinds of avocations were surely absent in the Vedic age.

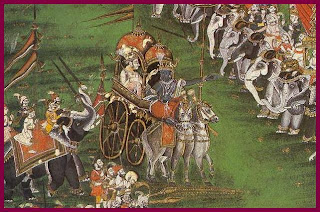

Earlier of the two great Sanskrit epics of India, the Mahabharata (other being the Ramayana) is written earlier than the other. Considered to be the longest single poem in the world literature, the epic is traditionally ascribed to the sage Vyasa, though it incorporated many episodes in the later centuries. As the poem stands today, it contains about 90, 000 stanzas, most of them of thirty two syllables.

Earlier of the two great Sanskrit epics of India, the Mahabharata (other being the Ramayana) is written earlier than the other. Considered to be the longest single poem in the world literature, the epic is traditionally ascribed to the sage Vyasa, though it incorporated many episodes in the later centuries. As the poem stands today, it contains about 90, 000 stanzas, most of them of thirty two syllables.